I am a prisoner, held inside my own head. It’s not the first time I am a prisoner. Really, this is not such a bad place, my head. It’s a mansion, in fact, a many-roomed marvel. Each room contains a chapter of my life, and oh, I’ve lived a long one. Too long, some of them think, but that’s another story, not mine. Too many sights I’ve seen in my day. They’ll die with me.

Is that what’s wrong with me? Am I dying? They won’t tell me, but I think they know. After you died, Hank, I wanted to die, too. Now I’m not so sure. I’m not sure about anything. Uncertainty has become my prison warden.

I wish I could ask someone, but words are not mine anymore. Words float around loose inside the dark inside my head. I can’t pluck the words from the dark and roll them off my tongue in a way that they can understand. I can’t make my hand work so that I can capture words on paper. Oh well. Words won’t help me move about in the rooms of my head.

Words… Words…

I don’t need words to tell you what you already know. I love you. First and foremost. Always and forever. That’s what families are for, for loving. If you know nothing else, you will always know this one thing.

It’s the rest of it that I can’t tell. The rest, that I’m burning to tell. Perhaps for now those stories are best left locked in their rooms, with me, inside my head. No one would believe me, even if I could make the words work once again.

* * * * *

Rosamonde Ayers Berryhill was a natural-born storyteller. That skill had always made her a hit at all the dinner parties. She sparkled more than the champagne in her flute. She knew the right questions to ask, when to tease, when to laugh, when to go on, and most important, when to be quiet. She used her body to help her. She knew when to lean forward, as if confiding a secret, and just how close to go, depending on whom she’d captivated with her story. She knew when to shiver, shaking her delicious curves in all the right places, when to seduce with her extra-long eyelashes, when to touch her listener and when not to. Her skin felt like silk, and she always smelled just right – fresh, with a hint of the wild. Like a sunny meadow of daisies planted by God. To illustrate her stories, her piano-long fingers did a little dance that could hypnotize a snake charmer.

Back when Rosamonde was still just an Ayers, she charmed and seduced Hank Berryhill, and by the end of their first two weeks together, they’d found a justice of the peace to marry them.

Rosamonde never wanted her home to end up here in Hawaii, almost three quarters of a century later. She’d followed Hank around the continental United States, and enough was enough. Besides, she didn’t belong to the tropics. If it was such a paradise, why did people seek the cold of their air-conditioned homes? Back in the north, folks sought warmth. The Aloha state would always mean Pearl Harbor to her, the beginning of the end for Hank.

They had a good life together, nothing extravagant on Hank’s government salary. They didn’t need money to feel rich in those days when they had each other. Not even the kids, Melody and Barry, got in the way of their loving. Death managed to separate them eventually, but in the flesh only.

Hank died the year before Lani, their granddaughter, was born. Rosamonde came out for a brief visit to help with the new baby, and so Hank came along, too, in spirit, of course. Right away, he recognized the Berryhill spunk in the little spitball swaddled in pink. Lani and Melody were bound to mix about as well as nuclear fusion.

Hank’s hypothesis was tested and verified over the years. Lani would turn sixteen around the same time her mother was going menopause on her.

That year, Lani usually went to the beach with her boyfriend every day after school, because why wouldn’t she? World-class Waikiki was only a few blocks from home. She didn’t like the crowds of tourists there, but she figured they were better than the way her mother crowded her at home.

All that was bad enough, but then things got worse two days before Lani’s sixteenth birthday. That day, she decided to come straight home from school. And she caught her mother – Melody – in the middle of growing a pile of castoffs in the hall outside Lani’s room: rumpled clothes (all baggy and black – what’s wrong with kids these days?), loose CD’s and cracked jewel cases, stuffed animals that’d had their stuffing loved out of them, crushed tampons still in their wrappers, and her collection of dog-eared paperbacks from the dollar bin across town. Lani threw a fit like she’d never thrown before.

“What are you doing, MOTHER?” She always saved the formal word for her greatest disapproval of Melody.

“Home so soon, dear?” Melody said with a smile bright enough to sell toothpaste. “Did you have a nice day at school? Did Kapono bring you home in his father’s car? I hope you remembered to wear your seatbelt. You didn’t leave him sitting out there in the driveway, did you? When are you going to invite him in, so that we can meet him?”

“MOTHER! Are you going through my STUFF?”

“Lower your voice,” Melody said. “Grandmum will hear you. Your Uncle Caleb has just brought her home. He was babysitting her in his antique shop, you know, while I had an appointment I had to keep.”

“Gran can’t hear anything.” Lani scooped up an armload of rejects from the pile in the hall. “Get out of my room.”

Now, that just wasn’t true. Hank remembered how his Rosie could hear snowflakes fall every winter since that first, magical February of ’43, back when they met.

“It’s not your room anymore, dear. We’re putting Grandmum in here. You don’t mind, do you?”

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest slipped from Lani’s arms and thunked to the floor. She’d read it five times, and now she didn’t even notice it fall. She just left it there in the hall and stalked into her former room where she unloaded her things onto the fake wood floor as if she was staking out a claim.

Melody’s legs weren’t as long as her daughter’s, but she had more years of charm school under her belt. Without missing a beat, she floated over to Lani’s stake, knelt, and patiently picked up piece after piece.

“Grandmum can’t stay upstairs in my sewing room any longer,” Melody said, picking lint from the black pants and shirts as she draped them one by one over her arm. “We can’t trust her with stairs. This room is so much more practical for her, since it’s on the ground level and the bathroom is just down the hall.”

“Yeah, and it’s closer to the front door, too. Aren’t you worried about her wandering off?” Lani grabbed her clothes from her mother’s careful sorting and threw them on the unmade bed.

“Dear, I wish you would be more helpful.” Melody stood and rearranged the smile on her face, which she always did when she found herself having to look up at her daughter.

Lani folded her arms across her chest, which she always did to show her mother that she was bigger, even in the boobs. “That’s not the issue, Mother. No one ever asked me.”

“Where else could Grandmum go? She can’t stay on her own anymore, not after that last fiasco. Do you remember? When I had to fly all the way back to Baltimore to get her money back from that scammer who promised to fix her roof and didn’t? And I missed my connection in Denver and ended up spending more money than what Grandmum lost?” Melody sighed and breezed over to a wall of posters where she used her French manicure to pry loose the first piece of tape she came to. “Your Uncle Barry’s no use. What else could we have done but bring her here?”

“I’m not talking about whether or not Gran should live with us.”

“Then what’s all your fuss about?”

“Can’t you like ever ask before you go and do something?” In three strides of her long legs, Lani crossed the room and tore the poster from its anchor of tape and from her mother’s fingernails.

Melody did her best not to gasp, but a little puff of surprise slipped past her thick layer of lipstick, the shade of sunset. “Oh, too bad. That was your favorite singer, and now he’s ripped. Never mind. I can tape him up from the back side so that you won’t even notice.”

“Mother, he’s like so yesterday.” Lani crumpled a piece of the torn poster into a wad, assumed a basketball stance on the balls of her feet, and aimed her paper ball at the hoop over her door. Score.

“All right, dear. Let’s be reasonable, shall we? Don’t you want your Grandmum here with us?”

“That’s not the question, Mother.”

“You can sleep on the futon in my sewing room. We’ll have such fun! We’ll be like sisters. Best friends.”

“Why can’t you move your sewing into your room with you and Dad?”

“Oh, no, no, that just wouldn’t work, not at all. You’re not being rational. My sewing is a business, not just a hobby. It puts food on the table and buys these posters for you.”

“Jewell gave me that poster for my birthday last year.”

“Well, you see? That’s exactly what I’m saying. Without Jewell, I wouldn’t have a store where I could sell my designs, and you wouldn’t have your posters. Help me get the rest of these down, will you, dear? Then you can re-paint the walls, and everything will be all fresh and brand new for Grandmum.”

“Me? Why should I paint? It’s your idea, not mine.”

Melody sighed. “Are we going to have to go through this all over again?”

“Fine! I can tell when I’m not wanted.” Lani strode over to the child’s desk she’d outgrown four years ago, but she tripped over her own feet when she saw her papers stacked neatly and her pencils arranged by color in her pencil box. Her hand jerked back, as if a jellyfish had stung her. “What’d you do?” She screeched, then pounced onto the neat stacks, pawing through them and spewing papers onto the floor as her search grew more frantic.

“If you’re looking for your journal,” Melody said, “I moved it to a better place, rather than under all that mess, which I organized for you.”

Lani straightened and stared, stunned and speechless, at her mother. Tears streaked down her cheeks, plastering strands of hair together into ropes of blue-black, a reminder of her father’s diluted Hawaiian blood. Her face puffed to a ruddy shade of heat. She opened her mouth to spit out the insults that scrambled through her head, but only a sob came out. She tried again. “Where?”

“Finish helping me first, then I’ll show you.”

Lani whirled around and yanked open the drawers of her desk, one by one.

“Oh, it’s not there, so you can stop trying to find it. You can have it as soon as we’re done. C’mon and help me. Don’t you want your journal back?”

Lani pawed through folded notes and mad lib books and puzzle cubes and baseball cards and sparkle fingernail polish and loose jacks. Then a horn honked outside, and her frenzy deflated. With one last sniff, she ran from the room.

“I didn’t read it, if that’s what you’re worried about,” Melody called after her.

As Lani stormed down the hall, her grandmother was coming out of the bathroom. With split-second timing, Lani tacked to one side to avoid knocking Rosamonde over. Her grandmother was a lot more frail these days and seemed to shrink a little more, each time Lani saw her. Rosamonde sucked in her breath. Her eyebrows arched high, and a look of terror flitted across her face. Rosie never used to be afraid of anything.

“I’m sorry, Gran,” Lani said, steadying her by the arm.

“Home?” Rosamonde asked.

“Yes, I’m home,” Lani said, swooping down to pick up her backpack from the floor, where she’d left it by the front door. “But I can’t stay. I’ll come back to see you, Gran. I promise.” She bent to kiss her grandmother on the cheek, then she sailed out the front door and slammed it extra hard behind her.

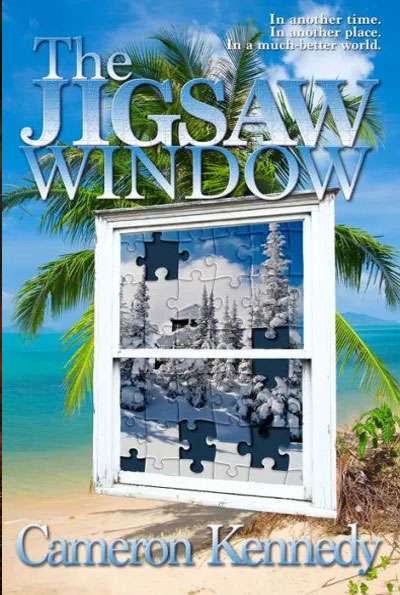

Rosamonde watched the door quiver. She could see all the splinters of glass shake inside the door’s little window. It wouldn’t take much to blow them apart into thousands of shards, like jigsaw pieces, once they started shaking like that. It seemed that she stood there a long, long time, watching. Waiting. Of course, she never was very good at telling time. Suddenly, Melody appeared at her side and smiled for her toothpaste commercial.

“Home?” Rosamonde said.

“Yes, Mom, you’re home. Aren’t you glad that you’re living with us now? We’ll take good care of you. This is your home now.”

But that’s not what Rosie meant, either. Hank knew, because he knew her better than anyone. Rosie wanted to know when she was going home.

Purchase this book online:

Also available for most other eReaders